movies, TV, writing

Redemption Arcs

In the book I’m currently working on, for the first time in my career I have scenes written from the perspective of one of the villains. He’s a henchman, not the big bad, and he’s the one sent out as the errand boy for the offstage villain. I haven’t decided yet if this guy is going to get a redemption arc, if maybe he’ll end up turning against the villain and joining the good guys, but pondering that has had me thinking about redemption arcs. I like them in theory. I belong to a religious tradition that’s all about redemption and believes that no one is beyond salvation, but I’m also picky about fictional redemption. I love the moment when a villain flips and joins the good guys, but I want to really feel the redemption, and I don’t want someone who’s done true evil to get off lightly.

A few years ago in a TV discussion forum, I jokingly came up with the redemption equation:

bad deeds=good deeds+remorse+suffering

The idea is that both sides of the equation have to balance for the redemption arc to be satisfying. If the good deeds, the remorse the character feels for the bad deeds, and the suffering don’t seem equal to the bad deeds the character has done, it doesn’t work. By suffering, I mean the consequences for the bad deeds, like prison time or other people not liking them; karmic payback; or mitigating circumstances (like a street kid taken in by the leader of a criminal gang). It doesn’t count if it’s suffering the characters bring on themselves. If you murder your parents, you don’t get suffering points for being an orphan, for instance. The worse the bad deeds are, the more the other things have to make up for it. It does get to the point where the bad deeds are so bad that you can’t imagine making up for it in a way that would allow an audience to accept a redemption. That doesn’t mean the character can’t ever be redeemed, but it may require the character to die for redemption to work. You can’t imagine that character just going on and hanging out with the other good guys.

Not that people haven’t written that. One of my biggest gripes with the TV series Once Upon a Time was the fact that the big bad from season one, someone who was shown to have casually murdered innocents because she was having a bad day and who cursed an entire civilization, was crowned Queen of the Universe by her former victims in the series finale, after she’d spent most of the series being friends with her former victims — and in spite of her never apologizing or acknowledging the harm she’d done. She just stopped being evil, with no explanation for why she stopped, and she never actually changed her attitude.

And I think that’s key to the redemption arc. There has to be a reason the villain stops villaining, and usually it’s the “are we the baddies?” moment, when the villain realizes that they’ve been wrong. If they don’t realize that killing and torturing people is bad or that they were on the wrong side and their reasons for doing evil weren’t valid, why would they change?

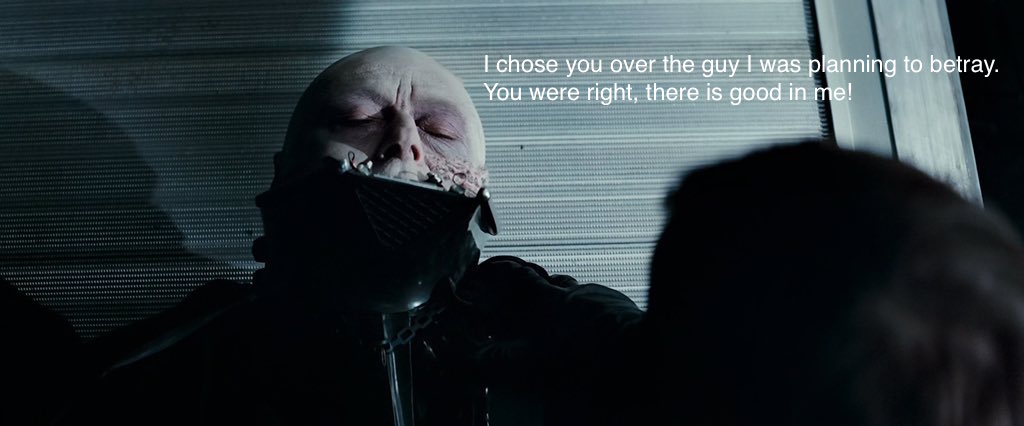

This is my problem with the “redemption” of Darth Vader (you knew this would get around to Star Wars, didn’t you?). I don’t know that we ever really got the moment of him realizing he was in the wrong. His redemption involved him choosing his son over the guy he was already planning to betray. That’s still a somewhat selfish move. He couldn’t stir himself to save entire planets, but when it was his son in danger, then he acted. Now, maybe I could be generous and say that hearing Luke refuse to kill him because he’s a Jedi like his father gave him his, “Whoa, I’ve been doing it wrong,” moment, but it’s still not super satisfying to me. It only really works because he immediately dies. It wouldn’t have worked if he’d lived and had become a good guy, hanging out with his kids. I’m not even that keen on the fact that he got to be a Force ghost. I don’t know if that’s the equivalent of Force heaven, but a last-minute change of heart doesn’t seem like it should allow him to hang around as a Force ghost, and I was especially irked when they re-edited it to be his younger self, when they didn’t also change Obi-Wan (and would Luke even have known who that random young guy who looked nothing like the man under the mask was?).

In the Star Wars world, they did a bit better with the redemption of Kylo Ren. It happened before the very end. He had a chance to really think about what he’d done, and he made an active choice to go help Rey — that wasn’t a spur of the moment decision. And, again, he died, giving up his life for someone else’s. He didn’t get to hang around with the good guys and live happily ever after.

As bad as Once Upon a Time was with that one character, they also managed to do it right. Their version of Captain Hook had some good reasons for being the way he was (explanations, not excuses). He had been wronged. He just went over the top in doing something about it. He had a big realization that he’d wasted his life in revenge and that people didn’t like him because he’d done horrible things. He even later counseled other villains about this and helped turn people away from becoming villains by sharing his advice. When he ran into former victims, he tried to atone and set things right with them. He got hit by a lot of karma on his way to redemption. It seemed like every time he did something bad, he’d get hit by a car, kidnapped, etc. And his suffering didn’t end when he turned good. He did some pretty big heroic acts as a good guy, so he had the good deeds to balance the bad. They did another good redemption arc on the Wonderland spinoff, with a character who was a villain for the first half of the series having a huge turnaround, realizing how badly she’d screwed up. She had to face some of her victims and learn how she affected them, and she had to work to earn the trust of the people she’d hurt, even after she turned good.

I do think it works better for the henchmen to be redeemed, the ones who were following orders or who’d been taught evil. It’s less believable when the big bad, the one who came up with and led the evil schemes, changes sides. Though it might make for a fun story if the big bad did change sides but all the henchmen were still on board with the previous goals and ended up fighting against the former big bad.

I think there’s room for my guy to be redeemed. He hasn’t done any large-scale evil. He’s the kind of weasel who stirs other people up to do his dirty work rather than doing it for himself. He’s suffered some, and he comes from a background that somewhat explains why he’s the way he is. He just made some poor choices in response to those circumstances. He’s enough of a jerk that I can’t imagine him joining the found family of team good guys, but he might realize the big bad has been using him and switch sides in the final showdown. We’ll see.